𝓒𝔂𝓷𝓲𝓬𝓲𝓼𝓶 𝓪𝓷𝓭 𝓟𝓸𝓼𝓽𝓶𝓸𝓭𝓮𝓻𝓷𝓲𝓽𝔂

𝒫𝓉. 𝟤 𝒦𝒾𝓉𝓈𝒸𝒽, 𝐵𝓊𝓁𝓁𝓈𝒽𝒾𝓉, 𝒶𝓃𝒹 𝒯𝒽𝑒 𝒫𝑜𝓁𝒾𝓉𝒾𝒸𝓈 𝑜𝒻 𝒜𝓊𝓉𝒽𝑒𝓃𝓉𝒾𝒸𝒾𝓉𝓎

Despite their adherence to integrity and authenticity, in Bewes’ terms, figures like Berubé and Wong are no less products of postmodern cynicism than are D’Souza or Trump. “Cultural obsession” with sincerity is a product of “collective social anxiety around authenticity” (Bewes 50); the “fetishization of authenticity” is a direct byproduct of late-20th century subjective fragmentation (50). McDonald’s’ corporate decision to drop “Have a nice day” in “favour of grater staff ‘spontaneity,’” and The Enlightened Tobacco Company’s “Death” brand cigarettes, to Bewes, are equally “banal instances of a retrospective idealism” (51). They are blunt, unsophisticated “attempts to expunge the signifier from the semantic equation” and disavowels “of the contingencies of representation” (51). The ham-fisted appeal to spontaneous sincerity on the part of McDonald’s as well as the Enlightened Tobacco Company’s “camp, ironic parody” are appeals to a “cheap literality” that lend commodities “an air of transparency, of neutrality” (50-51).

To strive for immediacy (in communication) is to express skepticism toward semiosis: it is an attempt to eliminate the boundaries between interior and exterior, private and public, thought and speech, intent and expression. The interrogation of sincerity, authenticity, and integrity is also the interrogation of representation as such. Desire for immediacy overturns faith in mediation – this is born of a fragmented, relativistic atmosphere, which Thorstein Botz-Bornstein calls deculturation. Deculturation takes place “when a particular group is deprived of one or more aspects of its culture” (Botz-Bornstein 2). Accelerated and spread globally by neoliberalism, modernization, a technologically powerful, but culturally weak force, worked to delegitimize inherited forms of mediation and representation. Botz-Bornstein points to the rise of fundamentalist religion, which sidesteps ordained ecclesiastical representatives in favor of “pure truths unmediated and unfiltered by cultural components” and treats “religion as a self-sufficient takeaway cult,” as a “flagrant” consequence of deculturation. The cultural obsession with sincerity is a response to postmodern deculturation that attempts to do away with systems of representation that are no longer to be trusted.

In its cruder forms, the pursuit of immediacy takes the form of kitsch, which Botz-Bornstein ties directly to deculturation. Kitsch relies on “exaggerated sentimentality, banality, superficiality, and triteness” (43); it is marked as “a tasteless copy of an existing style” or “the systematic display of bad taste or artistic deficiency” (43). Cynical kitsch does away with questions of eloquence, artistic virtuosity, and stylistic distinction; it instead embraces the bland, the trite, and the mundane as means to pare away the trappings of representation in favor of direct, authentic communication.

Borrowing a term from Harry Frankfurt, Botz-Bornstein likens kitsch to bullshit, which he defines as “an alternative aesthetic truth” (quoted in Botz-Bornstein 44) – bullshit is not a “non-truth (a lie) but a new truth aspiring to coexist with other truths” (44). The postmodern condition that Bewes tracks is fertile ground for both kitsch and bullshit, which “thrive in situations of deculturation” (44). Both McDonald’s effort to do away with the stilted formality greetings and farewells dictated by corporate policy and the winking frankness of The Enlightened Tobacco Company managing director CEO’s comment that “Death Trap customers will be buying a full, honest pack of cigarettes, not a pack of lies” are kitsch bullshit pandering to the Cult of Authenticity. For all of their pretense to candor, they are still distortions that create “alternative realities” masked by “easiness, nonchalance, innocence, and – sometimes naivete” (45). A McDonald’s employee remains compelled to speak to customers in a way that is accommodating and professional, regardless of the slack they may receive for “spontaneity;” The Enlightened Tobacco Company’s ad-copy remains a manipulative sales tactic, regardless of its putative probity. Brute appeals to authenticity, especially in the hands of corporate advertisers, cynically capitalize on anxieties surrounding deculturation, metaphysical uncertainty, and semiosis.

The cynical Cult of Authenticity, according to Bewes, is also marked by a strong strain of depoliticization — a depoliticization that, on its face, claims to cleanse civic discourse of disingenuous bullshit. Citing Tony Blair’s reorientation of the British Labour Party in the 1990’s (specifically, his 1994 conference speech), which he sees largely as an attempt to launder political rhetoric from civic discourse, Bewes finds three main tendencies that attempt to restore the language of integrity to the party: (1) Blair argues that Labour represents “all British people, ‘across the nation, across class, across political boundaries” (69); (2) he favors “values” over “policies” (72); and (3) he appeals plain spoken sincerity (“Let us say what we mean and mean what we say” [quoted in Bewes 75]). Less important than the party’s reconfiguration itself is “the degree to which and the reasons why the assurance of sincerity has become such dominant theme in contemporary political discourse” (74). Bewes chalks this up to current cultural anxieties, specifically, those surrounding sincerity, as well as a “perceived political cynicism of the electorate at large” (74).

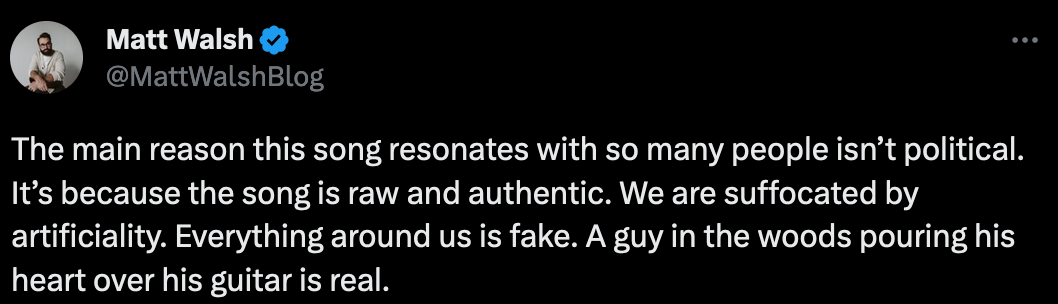

Following the release of Virginia country singer Oliver Anthony’s viral performance of “Rich Men North of Richmond,” conservative political commentator Matt Walsh simultaneously gave voice to the cultural obsession with sincerity as well as the political cynicism indicative of postmodernity. Praising Anthony’s performance, Walsh tweeted, “The main reason this song resonates with so many people isn’t political. It’s because the song is raw and authentic. We are suffocated by artificiality. Everything around us is fake. A guy in the woods pouring his heart over his guitar is real” (Walsh). He continues, “Most music is essentially computer generated. Movies are CGI. The news is fake. Most of what you see on social media is fake. AI, photshop, deepfakes, etc. We crave authenticity because we don’t have nearly enough of it” (Walsh). David Harris, of the Christian Ministry organization TruthScript, also praises Anthony for his authenticity: he contrasts him to hick-lib country performers such as Tyler Childers, whose “ethics are a form of leftist colonization” (Harris). Childers, who is “from, but no longer of, Appalachia” in “terms of values and a basic moral vision” (Harris), has compromised his authenticity, and, such a compromise, according to Harris is to “gain socially, gain financially, and gain opportunities” by making rural conservatives “feel surrounded, discouraged, and despondent” (Harris). New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff responded to the song with a similarly, cynical depoliticization, rebuking liberals for “[dumping] on a blue-collar guy who highlights ‘folks in the street, ain’t got nothin’ to eat” (Kristoff). Despite Anthony’s condemnation of the use of tax programs to pay for junk food, Kristoff goes on to write that “Some of his lines aren’t so different from elements in F.D.R’s speech about ‘the forgotten man or in Robert Kennedy’s elegy for ‘the shattered dreams of others” (Kristoff).

Walsh, Harris, and Kristoff’s responses to Anthony are cynical responses in line with the depoliticized pursuit of authenticity present in Tony Blair’s program. Kristoff leans directly into the same “inclusivist fantasy” as Tony Blair in his attempt to round off the harder political edges of the song to find abstract values in line with the politics of FDR or RFK. (Bewes 76). It is an aspirational universalism that denies representation of “the interests of one section of society more than another” (69). Kristoff tries to look through the song’s overt politics (and blindly ignores its conspiratorial elements) to underline its blurry, generalized values. However, in doing so, Kristoff extrapolates the song’s message to so general a level that it evaporates into banal platitudes (respect workers, show some empathy, etc). It is the direct inverse of the Kelvinistic pragmatism practiced by figures like D’Souza and Trump, which runs aground on the depoliticized civic niceties; his diplomatic, even handed pragmatism has a “levelling and neutralizing” effect that favors mealy mouthed, kitsch bullshit over concrete political conviction.

Walsh’s blanket condemnation of contemporary media is a turn away from “the alienated, representative, mediated world of the public sphere” (Bewes 77). He brackets the song’s politics and attributes Anthony’s success to his raw authenticity. However, the polarized response to the song broke largely along ideological lines: it was met with praise from conservatives and praise from liberals (and bemused confusion from the left). Anthony faced backlash after an interview in which he described America as “the melting pot of the world,” with one Twitter user suggesting that “companies are testing the waters to see if they can create fake republican singers to make more money off the republican demographic” (@LomzLomz). To attribute Anthony’s resonance wholly to a vague sense of integrity, especially when its resonance (or lack thereof) had such clearly defined political contours, is a cynical appeal to the Cult of Authenticity.

Harris, who, despite his openly polemical position, proves to be the most depoliticized cynic of the three commentators. He contrasts contemporary hick-lib performers to liberal or left-leaning classic country singers. Unlike the instrumental, political element of hick-lib figures, whose work eschews “the language of interpersonal relations” for “the crueller, radically insensitive language of realpolitik” (Bewes 68), for Harris, an “authentic” representative of like John Denver, despite his liberalism, embodies values. Denver’s advocacy wildlife preservation remains authentic because it was tied to “maintaining the distinct ways of life that the regions’ people had been living for decades or even centuries” (Harris). Harris simply extricates inconvenient radicals like Woody Guthrie and Steve Earle as inauthentic “singers and songwriters with distinctly left-wing appeal who often had much more commitment to communist and socialist dogmas than to their small hometowns” (Harris). Though Harris encourages up and coming singers to “sing about the old, sing about the new. Write about struggle, joy, heartbreak, and victory” (Harris), to be authentic, this must be done using a strictly “depoliticized vocabulary” that conceals “the power-political’ nature of all social relationships” (Bewes 68). Harris implicitly equates left-of-center ideology with politics, and right-of-center ideology with values: to lean left is to lean toward transactional instrumentality; to lean right is to lean toward home-grown virtue.

Explicit political expression, such as protests against the war in Iraq from moderate liberals like Linda Ronstadt or The Dixie Chicks becomes an opportunistic expression of power politics. In contrast, Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue,” in such a framework, becomes an expression of “The American Way” as an authentic value: Keith, who also did not support the war, exchanges the discourse of politics for the discourse of values: “I don’t apologize for being patriotic […] if there is something socially incorrect about being patriotic and supporting your troops, then they can kiss my ass on that […] and that has nothing to do with politics. Politics is what’s killing America.” The appeal to value over politics, whether from a politician, such as Blair, from a performer, such as Keith, or from a commentator, such as Harris, is a cynical refusal to engage with the world as it is because they so prioritizes the way things should be that they disengage entirely with the way things are.

The Cult of Authenticity, as a political project, is a skeptical melancholy that seeks to “eradicate the boundaries which seem to inscribe privilege and differentiation as social ineluctables” and replace “different spheres of life with one all-encompassing and democratic realm: society” (Bewes 102). One’s motives must remain pure; it is better not to act than to risk contaminating one’s integrity by engaging with the world as it is. The upshot here, is a paralytic combination of tristitia (sorrow) and desidia (idleness) masked in the garb of hope and high expectations. The medieval Christian theologian John Cassian describes a similar condition in monks plagued by the “noonday demon” of acedia (sloth), that led to “a disdain for the brothers who live with him, who now seem to h im carless and vulgar,” made him “inert before every activity that unfolds within the walls of his cell,” led him to “[plunge] into exageratted praise of distant and absent monsteries,” and ultimately left him in an inert, “senseless confusion” (quoted in Agamben, 3-4). Giorgio Agamben explains that such a condition stems not from “the awareness of an evil, but on the contrary, the contemplation of the greatest goods” (Agamben 6). Adherents to The Cult of Authenticity withdraw from the world, from action, and from politics when faced with “a goal that reveals itself in the act by which it is precluded and that is there for so much the more obsessive to the degree that it becomes unattainable” (6). Possessed by Cassian’s noonday demon, postmodern politics aims “to put a hold on the hazardous exercise of political rationality in the quest for metaphysical stability” (Bewes 8). The cynical search for authenticity is a tool of deferral that allows the noonday demon to defer “hazardous exercise” indefinitely.